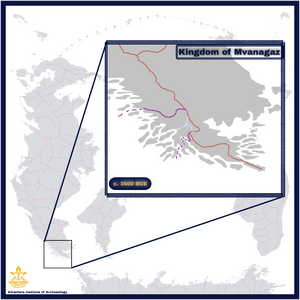

Kingdom of Mvanagaz (Pacifica)

Overview

The Kingdom of Mvanagaz (c. 4370 BCE – c. 2197 BCE) was one of the earliest consolidated states in Greater Krauanagaz, centered in the Mvanagaz Highlands of southern Cordilia. It represented a critical phase in the evolution of Krautali civilization, marking the transition from clan-based highland polities to centralized monarchy. Alongside its southern rival, the Dominion of Alkantara, Mvanagaz shaped the early political, economic, and cultural landscape of the region for nearly two millennia.

Foundation and Early Development

The kingdom emerged around 4370 BCE, when a coalition of Krautali highland clans unified under a monarch who consolidated authority through both kinship and conquest. This unification was facilitated by the geography of the Mvanagaz Highlands: fertile valleys supported intensive agriculture, while surrounding ridges offered natural defenses. The region was also rich in mineral resources, including copper and obsidian, which underpinned both local economies and long-distance trade. These advantages made Mvanagaz a hub for overland commerce, particularly for merchants seeking safer routes than the treacherous mountain passes or maritime corridors leading to Alkantara.

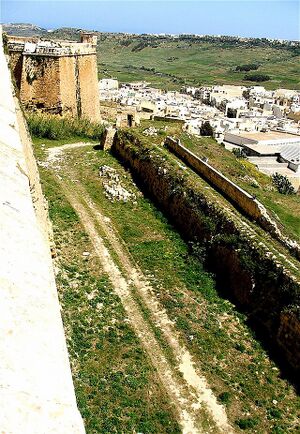

Archaeological evidence suggests that Mvanagaz was organized around a network of fortified mountain citadels, which functioned as both administrative centers and defensive strongholds. Regional chiefs, often drawn from influential clans, were subordinated to the king but retained limited authority within their territories. Inscriptions and surviving records indicate that the monarchy claimed divine sanction, associating its authority with local mountain and fire deities later integrated into the broader Tiribtalla pantheon. This blending of spiritual and political authority legitimized the monarchy and reinforced loyalty among subject communities.

Religion and Culture

Religious life in Mvanagaz centered on the worship of natural forces, particularly mountain peaks, rivers, and volcanic fire, which were perceived as divine manifestations of protection and renewal. These beliefs were gradually absorbed into the wider Tiribtalla system, which spread across Greater Krauanagaz in subsequent centuries. Early ritual sites, including highland shrines and open-air altars, suggest that kings often acted as priest-rulers, mediating between their people and the divine. Material culture from the period such as carved stone stelae, ceremonial weapons, and intricate pottery, reflects both local traditions and influences from neighboring regions, attesting to Mvanagaz’s role as a crossroads of trade and cultural exchange.

Relations with Neighboring States

Throughout its history, Mvanagaz maintained a tense rivalry with the Dominion of Alkantara to the south. While Alkantara relied on maritime trade and coastal expansion, Mvanagaz leveraged its control of highland passes and interior routes. This competition often led to conflict, with fortified citadels serving as focal points for military campaigns. Despite such rivalries, the two states shared cultural and religious influences, suggesting both exchange and contestation over centuries. Mvanagaz also exerted influence on smaller highland and riverine communities, some of which became tributary states or buffer zones between the kingdom and its rivals.

Decline and Legacy

By the late 3rd millennium BCE, the Kingdom of Mvanagaz began to fragment under pressures from internal dissent, shifting trade routes, and the rise of new lowland powers. Archaeological layers indicate a decline in citadel construction and evidence of widespread burning, pointing to both external invasions and internal conflict. Around c. 2197 BCE, the kingdom collapsed, its territories absorbed into successor states and rival polities.

The legacy of Mvanagaz endured, however, through its contributions to Krautali statecraft, religion, and cultural identity. Its mountain citadels, some still standing today, influenced later fortress architecture in Greater Krauanagaz, while its integration of local deities into the Tiribtalla pantheon helped shape the region’s enduring religious traditions. Today, the memory of Mvanagaz survives in oral traditions, mythic genealogies, its ancient capital city, and archaeological remains scattered across the highlands, offering a glimpse into one of the formative civilizations of southern Cordilia.

Rivalry with Alkantara

By the late 4th millennium BCE, the Kingdom of Mvanagaz had grown into a preeminent power of southern Greater Krauanagaz, directly challenging the maritime supremacy of the Dominion of Alkantara. While Alkantara’s influence was anchored in its coastal ports and seaborne trade networks, Mvanagaz commanded the lucrative overland corridors that connected the Alkantaran trade to the interior of Cordilia. This economic competition increasingly drew merchants and caravans away from Alkantara’s markets, threatening its long-standing dominance. The rivalry quickly extended beyond commerce, spilling into questions of territorial control, diplomatic influence over smaller states, and religious prestige within the Tiribtalla cultural sphere.

The tensions culminated in the early 3rd millennium BCE, when the King of Mvanagaz initiated one of the largest known military mobilizations of the early Krautali world. Chroniclers describe “hundreds of thousands” of troops marching south in 3021 BCE, supported by supply caravans and levies drawn from the highland citadels. The campaign aimed not only to subjugate Alkantara but also to secure access to its rich coastal trade hubs. Over decades of fighting, Mvanagazi forces pushed deep into Alkantaran territory, razing farmland and besieging fortified cities. The most notorious confrontation, the Siege of Alkantara (2987–2985 BCE), became a defining moment in Krautali military history. Despite their superior numbers, the armies of Mvanagaz were unable to breach the formidable fortifications of Alkantara’s capital. The prolonged siege strained both sides, draining manpower and resources and leaving swathes of the region in ruin.

Although Mvanagaz failed to capture Alkantara, the conflict did not result in a clear victory for either state. Instead, after years of attrition, the war ended in a negotiated stalemate. Under King Tkalla IV of Alkantara and King Mvani VII of Mvanagaz, the two powers concluded a peace treaty that established fixed borders, regulated cross-border trade, and codified a mutual non-aggression pact. This accord, sometimes referred to as the Treaty of the Two Thrones, is considered the earliest recorded diplomatic agreement in Greater Krauanagaz. Its provisions stabilized relations for generations, allowing both states to recover from the devastation while preserving their distinct spheres of influence.

The rivalry between Mvanagaz and Alkantara left a lasting imprint on the political culture of the region. Later Krautali historians cited the stalemate as a cautionary tale of hubris and overextension, while religious texts framed it as evidence of divine restraint upon kings who sought unchecked conquest. The memory of the wars continued to shape diplomatic traditions, with the treaty serving as a precedent for later accords between rival Krautali polities. In this sense, the Mvanagaz–Alkantara rivalry not only defined the geopolitics of its era but also laid the groundwork for the earliest concepts of balance of power in Krauanagaz history.

Political and Military Organization

The Kingdom of Mvanagaz operated under a hereditary monarchy that claimed divine mandate, with the king styled as both military commander and spiritual intermediary. While the monarch exercised supreme authority, governance was not entirely autocratic. A council of clan elders drawn from the leading highland lineages functioned as an advisory body, influencing matters of succession, resource allocation, and local administration. This balance reflected the kingdom’s origins in a coalition of highland clans, where loyalty to the throne was mediated through traditional kinship ties and obligations. The monarchy’s legitimacy rested almost entirely on its ability to command consensus among these clans while projecting power beyond the highlands.

Militarily, Mvanagaz was distinguished by its vast infantry armies, which were rallied from the rugged highland communities. Each clan was obligated to provide soldiers, weapons, and provisions in proportion to its size and wealth, creating a mobilization system capable of sustaining campaigns with large numbers of troops at its height. These forces were anchored in fortified mountain citadels, which doubled as administrative centers and supply depots. According to archaeological findings, the armies of Mvanagaz utilized disciplined infantry formations, equipped with spears, axes, and heavy shields. Though not as technologically advanced as Alkantara’s naval forces, the sheer numbers fielded by Mvanagaz made it a formidable adversary in land-based conflicts across the western peninsula.

Diplomatically, Mvanagaz alternated between aggressive expansionism and pragmatic treaty-making. Kings launched periodic campaigns against neighboring tribes and rival city-states to assert dominance and secure access to trade routes, yet they also engaged in formal diplomacy when prolonged conflict proved unsustainable. The peace accords with Alkantara, for example, reflected both the kingdom’s capacity for war and its recognition of the limits of overextension. Treaties often formalized spheres of influence, established tribute arrangements, or codified trade provisions, demonstrating that Mvanagaz was not merely a warrior society but a political entity capable of long-term statecraft.

Yet the kingdom’s power was also defined by its limitations. Unlike Alkantara, whose naval fleets gave it reach across southern Cordilia’s coasts and islands, Mvanagaz never developed a strong maritime tradition. Its dominance was confined to inland trade and overland warfare, which restricted its ability to project influence into distant regions or establish overseas colonies. This reliance on land armies ensured supremacy in the highlands and valleys but left the kingdom vulnerable to being outmaneuvered at sea, especially in its long rivalry with Alkantara. Even so, Mvanagaz’s organizational strengths, its ability to marshal vast infantry armies, maintain fortified citadels, and unite disparate clans under royal authority, secured its place as one of the defining powers of early Krautali civilization.

Cultural and Economic Life

The economy of Mvanagaz was deeply tied to the resources of its highland environment. Rich deposits of iron, copper, and gemstones provided the kingdom with both tools of war and luxury goods for trade. Archaeological evidence suggests that mining settlements dotted the highland valleys, connected by caravan trails that linked resource sites to fortified citadels. Agricultural production in the fertile valleys supplemented this resource wealth, with barley, millet, and legumes forming dietary staples. Livestock herding, particularly goats and sheep adapted to the rugged terrain, also played an important role, providing wool, meat, and secondary trade commodities. The integration of mining, farming, and herding created a resilient economic base that allowed Mvanagaz to sustain large armies and finance monumental building projects.

Trade was the lifeblood of the kingdom’s wealth and influence. Positioned between the Krautali lowlands to the south and the Lupritali mountain clans to the north and east, Mvanagaz became a central node in interior trade networks. Merchants established permanent exchanges where salt, grain, and crafted goods from the lowlands could be bartered for minerals, textiles, and livestock products from the highlands. These exchanges not only enriched the kingdom but also fostered cultural cross-pollination, bringing foreign religious practices, artistic motifs, and technologies into Mvanagaz society. In this way, the kingdom became both an economic hub and a cultural crossroads in Greater Krauanagaz.

Culturally, Mvanagaz cultivated a distinctive highland identity rooted in both its environment and its syncretic religious life. While Tiribtalla traditions provided a shared framework of gods and rituals, the people of Mvanagaz elevated their own cults of mountain spirits, fire deities, and hearth gods, reflecting the rugged landscapes in which they lived. These localized beliefs emphasized themes of endurance, fertility, and protection, aligning well with the kingdom’s militarized society. Kings often associated themselves with sacred peaks or claimed divine favor from volcanic fire, reinforcing their legitimacy through both Tiribtalla cosmology and uniquely highland symbolism.

The material culture of Mvanagaz reflected these religious and social values. Stone fortress construction became a defining feature of the kingdom’s landscape, with citadels not only serving as military strongholds but also as centers of administration and ritual. Monumental stelae, carved with inscriptions and symbolic imagery, commemorated royal victories, divine blessings, and clan contributions to the monarchy. These monuments, alongside fortified architecture, stand today as some of the most enduring legacies of the kingdom, offering insight into its political organization, religious life, and cultural distinctiveness.

Decline

By the early 3rd millennium BCE, the Kingdom of Mvanagaz had begun to show signs of deep strain. Centuries of intermittent conflict with Alkantara, particularly the costly invasion campaigns and the protracted Siege of Alkantara, left lasting scars on the kingdom’s economy. Resources once devoted to mining and trade were increasingly redirected to support military mobilizations, draining the treasury and weakening commercial networks that had sustained the highland citadels. Agricultural yields also declined as farmland was abandoned due to population losses and the disruption of traditional labor systems, creating food shortages that further destabilized the realm.

Political unity, once the kingdom’s greatest strength, began to erode in this climate of hardship. Rival noble clans, many of whom had provided the monarchy with soldiers and resources in times of war, grew resentful of the crown’s weakening authority. Clan elders, once the king’s closest advisors, began to assert greater independence, turning fortified citadels into power bases for their own regional ambitions. This decentralization of authority left the monarchy increasingly unable to project power across its territories, weakening its control over the kingdom.

By 2210 BCE, the balance of power in Greater Krauanagaz was shifting rapidly. External threats compounded Mvanagaz’s decline, with rising city-states such as Kevluarital, Koralaavin, and Zaari emerging as new centers of power, absorbing territories that once acknowledged the authority of the highland monarchy. At the same time, Lupritali and ascending Krautali tribal confederations took advantage of the weakening state, expanding into its borderlands and establishing footholds in former Mvanagazi domains.

Around 2197 BCE, the kingdom collapsed as a centralized monarchy. What followed was not a sudden disappearance but a gradual fragmentation, as Mvanagaz’s territory splintered into smaller polities ruled by local chiefs, ambitious nobles, and emerging city-states. While the monarchy itself faded, its legacy endured in the fortified citadels that dotted the highlands, in the treaties and traditions it pioneered, and in the cultural memory of later Krautali polities who looked back to Mvanagaz as a model of early highland statecraft.

Legacy

Although the Kingdom of Mvanagaz disappeared as a centralized state by the close of the 3rd millennium BCE, its imprint on the cultural and political fabric of Greater Krauanagaz remained profound. As one of the earliest highland monarchies, it established enduring models of governance that later polities would draw upon, particularly the combination of hereditary kingship supported by councils of clan elders. This balance between royal authority and communal consultation shaped later highland traditions and persisted in various forms across successor states and tribal confederations.

The kingdom’s military reputation also cast a long shadow. Its near-destruction of Alkantara during the late 4th millennium BCE wars elevated Mvanagaz to legendary status among later Krautali chroniclers, who depicted the highland kings as near-mythic warrior rulers commanding vast armies. Even though the campaigns ultimately ended in stalemate, the scale and ambition of Mvanagaz’s mobilizations became benchmarks by which subsequent conflicts were measured. To this day, the “Siege of Alkantara” remains one of the most frequently cited episodes in early Cordilian military history.

Religiously and culturally, Mvanagaz blended Tiribtalla traditions with unique highland religious beliefs. These practices not only enriched the diversity of early Krautali religion but also laid foundations for the distinctive regional identity of the Mvanagazi Highlands. Archaeological remains, stone citadels perched on cliffsides, monumental stelae carved with royal inscriptions, and burial sites associated with fire rituals, testify to the vibrancy of this tradition. Such sites became touchstones for later highland communities, linking their own identities to the grandeur of their ancient predecessors.

In the centuries after its fall, Mvanagaz was remembered less as a failed kingdom and more as a lost golden age. Later historians and poets of Krauanagaz frequently romanticized it as a land of noble kings and unyielding warriors, contrasting its grandeur with the fractured politics of their own times. This cultural memory endured into the modern era, with Mvanagaz's ancient capital still bustling with life, as a major urban center of the Krauanagaz Federation, where the kingdom’s legacy continues to inform local identity, pride, and historical consciousness.